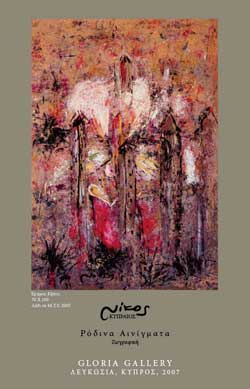

the Flowers

The Flowers series was painted during 2007

Abundand Mercy, Tactile Energy, and the Transendent Flower of Life

A Tribute to Nikos Kypraios

Robert C. Morgan Ph.D.

With the ambiguity of styles, hyperbole, and rancorous affectations that hover through the international art world, it is a solemn and comforting pleasure to encounter works of art that feel intelligent, sensuous, and real -- something that is not only called “art,” but lives according to the signifiers of joy and abundance. I am reflecting on a point of view on art that belongs to Nikos Kypraios – a painter who does not disengage himself from the vestiges of the creative past, but employs those vestiges at the source of his own aesthetic making. The paintings of Kypraios resonate with an aesthetic impulse as if to signify moments of clarity within the complex circumstances of normative existence. Living in an age of simulacra – to cite the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard – is to endure a condition in which most of what we encounter is mediated by the power of advertising and is willfully given over to fakery. According to Baudrillard, we exist in a time where reproductions have replaced originals. We consider the problems of the natural environment in this way. We view the conservation of historical artifacts and the preservation of significant architecture, whether from the ancient past or from early Modernism, as removed from the necessities of everyday life. Not only does the simulacra relate to the environment and to architecture, it also relates to the art of painting -- the human tactile means by which Nikos Kypraios imagines his landscape scenarios. We might think

of his paintings less in terms of simulacra, than as a phenomenon bestowed upon us by the forceful presence of an immense painterly intelligence.

Painting is no longer considered a window on life, as it was taught by Claude de Lorraine in the seventeenth century, and eventually absorbed into the French Academy. Nor is painting a mirror of the simulacra so rampant in the late twentieth century when Postmodernism was all the rage. The most interesting and vital painting today is not found in glossy magazines. Rather it exists in a kind of seclusion, in faraway places, unencumbered by the technological transformations of urban life – in places like the island of Samos or in the hidden neighborhoods of Athens where Nikos Kypraios divides his time. The real painting of today travels inward where it speaks on a more intimate level. It offers us a subtle visual (sometimes optical) means by which to re-evaluate our position in the world, our ethos. Such painting reveals the possibility for opening unknown thresholds of time and space – lost avenues of haptic knowledge -- as human beings move forward into the twenty-first century.

Nikos Kypraios is interested in nature and in the spiritual depths derived from nature – those depths that take us to the very core of our being. His paintings are neither windows on a detached world nor are they mirrors that reflect the banalities of the simulacra. In recent months, Nikos has painted flowers that offer a symbolic narrative, an allegory on how we might we might prevail and, most significantly how we might discover the source of joy in life. They are paintings of abundant mercy that move us from the immanent world of everyday matter to a new and vital transcendent energy that seeks resolution through intimacy. They are paintings that envision a sense of being within the perception of common things and within the hearts of ordinary people who hold the potential to affect our way of seeing.

We know that when Paul Cezanne painted nature at the beginning of Modernism a century ago, he was thinking in terms of the future, of the structure of reality is a way that would transform itself. Just as Cezanne concealed the present within the domain of nature, Nikos Kypraios conceals the truth in images of flowers – roses, lilacs, orchids, and tulips. His flowers appear innocent on first glance until we notice the background of decaying trees, lifeless forests, haunting skies, and the sexualized flowers that beckon us towards life. Nikos foregrounds orchids, but most often, roses – or just a single rose -- as if it were meant to carry the burden of humanity’s joy and grief in a single instant. There are paintings in which barbed wire holds the flower in check, keeping the rose or the tulip from extending out into the world of transcendent joy. The flowers of Nikos have no vases. They are gigantic flowers stranded in a foreign place, a war-torn forest, or isolated on a desecrated landscape. These paintings relate to the Burnt Forest series by Nikos where tragedy appears immanent unless human love and generosity intervene. Occasionally, Nikos will paint a woman’s face in a window peering out on to the landscape. What does this mean? Where do we go from here?

As in the work of all great painters, Nikos admits a personal (intimate) as well as a gregarious (social) meaning. The intentions of the artist reveal sensitivity both political and romantic, a place where the interior aspirations of the artist move toward enriching the meaning of existence. Often these seemingly opposing elements connect at some point. Either they connect through the symbolic flower – the rose, for example -- either as a liberating force or as an imprisoned spectacle. Several paintings reveal this conflict. The rose is either surrounded by barbed wire or impeded in some other way. There is also another possibility -- that the rose will emerge without deference to a singular meaning. The rose becomes the rose – a sign more than a symbol. Even further, one might recall the passionate statement by Joseph Beuys who expressed years earlier (1972): “We cannot do it without the rose.”

What can we not do? This is a question shared by both Nikos and Beuys. Can the rose evolve through interior necessity and outer circumstance as a sign of being or as a modulation towards becoming? Can the rose exist in the wake of a transition from one level of understanding to another? Is the rose, in fact, a passage between the material and the spiritual worlds?

I give credit to Nikos who does not impose a statement of meaning on his paintings, but who, as an artist, opens the threshold toward meaning through suggestion. These paintings of flowers give us more than a lyrical nuance. They are paintings that hold a tremendous force, an insistence that we must pay attention to the impulse of deterioration as much as to the quality of life. Materialism is less a reprieve from suffering than a denial of all that makes life important. In this sense, Nikos is a painter of the real – that is, what exists in terms of the real, beyond the surface, beyond appearances, and far beyond the superficial artifice of the simulacra. Nikos’ paintings are both signs and signifiers. They exist at the substratum of language. They are the first utterance – the place where we need to go in order to find the solace and happiness of living. Nikos Kypraios paints a symbolic world of indifference where it is still possible to share and enjoy the fruits of our simple, persistent labors.

____________________________________________________________

Robert C. Morgan is a Renaissance figure and leading international critic in contemporary art. The author of many books, and literally hundreds of essays and reviews, Dr. Morgan is a frequent lecturer and curator on the international circuit and is Professor of Fine Arts in the Graduate Program at Pratt Institute in New York.